Learning to accurately throw Paper Planes using Reinforcement Learning

This is a shortened version of the full project report, highlighting my contributions to the project. The full report can be found here.

Abstract

This work presents a novel approach to optimizing paper plane throwing using reinforcement learning and trajectory encoding. We introduce a method that combines a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) for encoding paper plane trajectories with a Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm to learn optimal throwing strategies. Our approach dynamically adapts to the unique aerodynamic properties of randomly generated paper plane designs. We explore two training scenarios: a one-step setting with a plane store and a multi-step setting with episode-based trajectory accumulation. Our experiments show that incorporating information from previous throws improves performance, particularly when generalizing to unseen plane designs.

Introduction

Robotic manipulation tasks often involve complex dynamics and control challenges. One such intriguing task is for a robot to accurately throw paper planes at a target. Despite its apparent simplicity, this task requires accurate determination and execution of initial launch conditions, considering the aerodynamic properties and inertial parameters of the paper plane. The challenge of robotic paper plane manipulation has attracted recent attention in the field. For instance, Tanaka et al. [1] demonstrated a robots' ability to fold paper planes. However, the precise launching of these planes remains an open problem. This task encapsulates core difficulties in robotics: real-time adaptation to object properties and precise control of launch parameters. By addressing these challenges, we aim to advance techniques applicable to a wide range of dynamic object manipulation tasks. This work focuses specifically on learning the initial conditions required for successful throws. To address this challenge, we introduce an episodic reinforcement learning (RL) framework that aims at determining the optimal initial velocity and orientation for launching the plane. It learns from observed trajectories of past throws, utilizing a MuJoCo simulation environment [2]. Key aspects of our approach include:

-

RL Environment: We design a RL environment in which the robot's actions, setting the plane's initial velocity and orientation, determine its trajectory.

-

Domain Randomization: To improve generalization and facilitate potential transfer to real-world robotic systems, we randomize the target's position and the plane's properties, ensuring robustness across different conditions and reducing the sim-to-real gap.

-

Latent Trajectory Embeddings: A Variational Autoencoder (VAE) [3] generates latent embeddings of the paper plane's past trajectories. These embeddings capture patterns in the plane's flight behavior, which indirectly reflect its aerodynamic properties without explicitly modeling them. By learning from these trajectory patterns, the robot can adapt its throwing technique to handle each specific plane more effectively.

-

Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) Algorithm [4]: We employ the SAC algorithm to learn the optimal initial conditions for launching the paper plane. Specifically, this involves determining the ideal initial orientation and velocity of the plane based on the current configuration of the environment and the latent embeddings of past trajectories.

By leveraging knowledge from previous throws, we can train an agent capable of handling a variety of paper planes. This approach eliminates the need for plane-specific agents. Most importantly, it enables our agent to adapt to unseen paper planes, using prior throws with the same plane as references.

Methods

This section details our approach to training a reinforcement learning agent to accurately throw paper planes. We begin by describing our domain randomization technique for generating diverse paper plane models. We then explain how we handle different plane behaviors using a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) to encode trajectory information. Next, we formulate the problem as a Markov Decision Process (MDP) and describe our chosen reinforcement learning algorithm. Finally, we outline our training process and the two distinct scenarios we use to evaluate our approach.

Domain Randomization

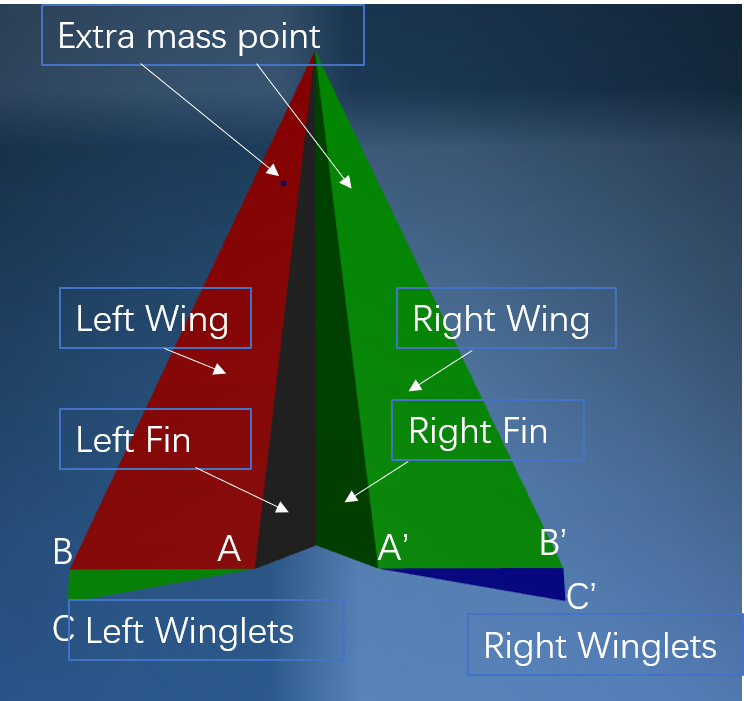

For our experiments, we randomize the angle and size of the paper plane's winglets (the flaps at the back of the plane, see Figure 1) to generate a diverse set of paper plane designs. The position of the target is sampled from a variable circle around the origin defined by a 3-tuple $(r_\text{target},\alpha_\text{target},z_\text{target})$ where $r_\text{target} \sim\mathcal{U}(4,10)$ [meters] is the radius of this circle, $\alpha_\text{target} \sim \mathcal{U}(-30, 30)$ [degrees] is the angle to the target relative to a reference orientation and $z_\text{target}\sim \mathcal{U}(0.5, 2.2)$ [meters] is the $z$-coordinate of the target. The interaction between these parameters can be seen in Figure 2.

Handling different plane behaviors

ue to the randomization of plane properties, each plane exhibits unique aerodynamic behaviors. To account for this variability, the agent is designed to learn about the plane's behavior from the trajectories of previous throws of the same plane. This approach avoids explicitly learning from the physical characteristics of the plane, which could exacerbate the sim-to-real gap. Such physical information is often difficult to obtain from real paper planes, making our method more applicable to real-world scenarios. Also, different combinations of physics parameters can result in the same behavior. For us, only the differences in behavior are relevant. Each trajectory point consists of the plane's position $\boldsymbol{p}$, velocity $\boldsymbol{v}$, and orientation $\boldsymbol{o}$. Given that trajectories can vary in length, they are not passed directly to the model. Instead, a latent embedding of the trajectory is generated to provide a compact representation of the plane's behavior. To create latent embeddings of the trajectories, we employ a Variational Autoencoder (VAE). The VAE processes sequences of different lengths and generates a latent representation that encapsulates the plane's aerodynamic behavior. The architecture of the VAE is as follows, see Figure 3 for more details:

-

Encoder: The encoder uses sinusoidal positional encoding [5], followed by a linear layer and a ReLU activation function. This is followed by multi-head attention [5], another linear layer with ReLU, and finally two separate linear layers that output the mean ($\boldsymbol\mu$) and logarithm of the variance ($\log\boldsymbol\sigma^2$) of the latent distribution.

-

Decoder: The decoder consists of a linear layer, sinusoidal positional encoding, multi-head attention, a LSTM layer, and a final linear layer. The input to the decoder is the latent representation $\boldsymbol{z} = \boldsymbol\mu + \boldsymbol\sigma^2 \cdot \epsilon$ with $\epsilon\sim\mathcal{N}(0,\boldsymbol{I})$.

We choose this architecture for our VAE model because it effectively addresses the challenges posed by variable-length trajectory data. The combination of Attention and LSTM enables the model to handle sequences of different lengths, capture long-range dependencies, and encode contextual information. The multi-head attention mechanism in the encoder allows the model to focus on relevant parts of the input trajectory, generating a rich and informative latent representation. The LSTM layer in the decoder helps maintain the temporal coherence of the generated trajectories by capturing and utilizing the relevant information from the entire sequence. Additionally, the sinusoidal positional encoding in both the encoder and decoder preserves the temporal structure and ordering of the points in the trajectory.

Markov Decision Process (MDP)

Our environment is modeled as a $\text{MDP} = (\mathcal{S},\mathcal{A}, \mathcal{R}, \mathcal{T}, \gamma)$. Every state $s\in\mathcal{S}$ is represented as a tuple $(z_\text{initial}, z_\text{target}, d, \mathbf{v}, \mathbf{z}_1,\dots,\mathbf{z}_n)$. The first components are a representation of the current setup, while the later components $(\mathbf{z}_1,\dots,\mathbf{z}_n)$ encode the trajectories of previous throws. $z_\text{initial}$ and $z_\text{target}$ are the z-coordinates of the initial and target position, $d$ is the Euclidean distance between the plane and the target, and $\mathbf{v}$ is the normalized difference between the plane's initial position and the target's position. Specifically, $\mathbf{v}$ is calculated by taking the elementwise difference between the target position and the initial position and normalizing this difference vector so that its components sum to 1. This state representation was chosen to ensure spatial invariance, allowing the model to generalize across different throwing scenarios regardless of absolute position in 3D space. $\mathbf{z}_1,\dots\mathbf{z}_n$ are the latent representations of the $n$ previous throws with the same plane. If fewer than $n$ throws have been recorded, the missing values are filled with zeros. An action $a\in\mathcal{A}$ is a 3-tuple, setting the initial orientation around the x- and z-axis and the initial speed in meters per second along this orientation. The reward $r\sim R(\cdot|s,a)$ is the negative minimal distance of the plane to the target during the whole trajectory. The specific implementation of the transition model $\mathcal{T}$ and the choice of discount factor $\gamma$ depend on the training scenario, as detailed in the Training Scenarios subsection.

RL Algorithm

For the reinforcement learning algorithm, we utilize the Soft Actor-Critic (SAC) algorithm from the stable_baselines3 library [6]. The agent learns to map the current state to an action that specifies the initial velocity and orientation of the paper plane.

Training

We use a Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with the following loss function: $$\mathcal{L}_{\text{VAE}} = \mathbb{E}{q_\phi(z|x)}[\log p_\theta(x|z)] - D_{\text{KL}}(q_\phi(z|x) || p(z))$$ where $q_\phi(z|x)$ is the encoder and $p_\theta(x|z)$ is the decoder. The VAE is initially pre-trained on a set of collected trajectories from our simulated paper plane models. Subsequently, it is trained online alongside the SAC model, but with different update frequencies. The SAC model updates after every episode. In contrast, the VAE is updated every $k$ throws (iterations). During each VAE update, we perform a training step on the trajectories collected over the past $k$ throws. After this VAE training step, these trajectories are discarded, and new data is collected for the next update. We explore two distinct training scenarios to evaluate our approach:

One-step setting with plane store

In this scenario, we maintain a plane store that contains the trajectories of previous throws along with their corresponding plane designs. When sampling a plane for training, we also fetch its associated trajectories. This approach ensures that we train with a full buffer of previous throws for all but the first 5 throws with each plane. The environment is modeled as a one-step setting, where each episode consists of a single throw, and the trajectories from previous throws serve as background knowledge for the agent. In this scenario, the transition model $\mathcal{T}$ is not explicitly used as each throw is treated independently. The discount factor $\gamma$ also does not impact the learning in this scenario. Figure 4 shows the interactions between all components during training.

Multistep setting with episode-based trajectory accumulation

In this scenario, we model our environment as a multistep setting. Each episode involves throwing a plane $n+1$ times, where $n$ is the size of the buffer for previous trajectories. Every episode begins with an empty buffer, which is gradually filled throw by throw. In this setting, the previous trajectories are an integral part of the state, allowing the agent to learn and adapt its strategy within each episode. For this scenario, the transition model $\mathcal{T}$ resets the plane to its initial position after each throw within an episode. We set the discount factor $\gamma$ to 0.99, giving higher importance to later throws which benefit from more accumulated trajectory information. The interaction between components remains consistent across scenarios, as illustrated in Figure 4 for the first training scenario. The key distinction lies in the handling of previous trajectories: rather than being stored separately in the plane store, they are incorporated directly into the state representation.

Experiments

Our experiments are designed to achieve two primary goals: (1) Identify a suitable range of parameters for randomizing the paper planes and (2) train a model on a set of planes using the parameters identified in step 1.

To establish a feasible range of paper plane designs for our study, we focus on optimizing parameters for the plane's winglet. Optimizing multiple parameters simultaneously can be challenging due to their complex interactions. By focusing on the winglet, we can more effectively manage the complexity of our experimental design while at the same time significantly influencing a plane's aerodynamic properties. The parameter selection process involves training our model on a diverse set of 130 randomly generated plane designs, with each design's agent undergoing 5000 iterations of training. This approach helps us identify a range of plane designs for which our algorithm can effectively learn to hit the target, while still allowing us to test our model's ability to generalize across different plane configurations within this established range. Next, we use planes generated from the identified parameter range to collect a set of trajectories, which are then used to pre-train our VAE. We set the dimension for the hidden linear layers to 16 and the dimension of the latent space to 8. As discussed in the methods chapter, each point in a trajectory consists of a 10-dimensional vector, so our input dimension is 10. We train the VAE for 15 epochs using the Adam [7] optimizer with a learning rate of $10^{-3}$. The pre-trained VAE serves as the initialization for all subsequent experiments. Finally, we train the SAC model, varying the number $n$ of previous throws considered. The SAC policy is initialized randomly, while the VAE is initialized using the pre-trained VAE. Both models are trained simultaneously, as described in the methods section.

Implementation of Training Scenarios

As described in the Methods section, we implement two distinct training scenarios: a one-step setting with a plane store and a multistep setting with episode-based trajectory accumulation. Here, we detail the specific parameters and implementation choices for each scenario.

One-step Setting Implementation: For the one-step setting we use a plane store containing 10 different plane designs. We compare a setting where each plane was associated with 5 previous throws to a setting where the agent has no knowledge about prior throws.

Multistep Setting Implementation: For the multistep setting we also use a set of 10 different plane designs. Each episode consists of $n+1$ throws, where $n = 5$. We train the agent for 15000 episodes. The buffer of previous trajectories starts empty at the beginning of each episode and is filled progressively.

Results

We present our findings from the two training scenarios: (1) a one-step setting with a plane store, and (2) a multistep setting with episode-based trajectory accumulation.

Scenario 1: One-step Setting with Plane Store

We conduct a comparative analysis of two distinct models: one that exclusively considers the environmental configuration, and another that incorporates both environmental factors as well as the trajectories of up to five previous throws. As illustrated in Figure 5, the model focusing solely on environmental information initially demonstrates superior performance. However, as the simulation progresses, the model that utilizes individual plane behavior data achieves better performance. The benefits of incorporating information from previous throws become even more evident when evaluating the models' performance on a set of 20 previously unseen paper planes. In these novel scenarios, the model that utilizes prior throw information consistently outperforms the model that relies exclusively on environmental configuration. Table 2 presents a comprehensive comparison of rewards across different models when tested on these unseen planes.

| Number of previous trajectories | Reward |

|---|---|

| 0 | $-0.4913 \pm 0.2461$ |

| 5 | $-0.3676 \pm 0.1827$ |

| Throw number | Reward |

|---|---|

| 1 | $-2.1175 \pm 1.2290$ |

| 2 | $-1.9544 \pm 0.8115$ |

| 3 | $-2.0931 \pm 0.8646$ |

| 4 | $-2.1432 \pm 0.5443$ |

| 5 | $-2.1525 \pm 0.9796$ |

| 6 | $-2.3030 \pm 1.0560$ |

Scenario 2: Multi-step Setting with Episode-based Trajectory Accumulation

Figure 6 illustrates the evolution of agent performance across multiple throws within a single episode, providing insights into how the accumulation of trajectory information impacts the agent's ability to optimize its throwing strategy. The performance of the first throw, which occurs without any prior trajectory information, initially shows an upward trend. However, we observe a subsequent decline in performance as training progresses. In contrast to the first throw, the second throw, which incorporates information from the trajectory of the first throw, demonstrates consistent improvement throughout the training process. Interestingly, the performance of throws that utilize information from multiple previous trajectories (throws 3-6) exhibits oscillatory behavior. Moreover, we observe that as the number of previous trajectories used increases, there is a trend towards decreased performance. Table 2 presents the mean rewards and standard deviations for each throw across 300 episodes, using 20 unseen paper plane designs. The data is aggregated from three different models trained with the same parameters but different random seeds. These results corroborate our earlier findings from Figure 6.

Discussion

Our study on paper plane throwing revealed distinct patterns in agent performance across two training scenarios. In the first scenario, the agent not using previous throw trajectories initially had an advantage, attributed to the effectiveness of a consistent throwing strategy. However, after about 8000 iterations, the model leveraging past throws demonstrated superior performance, likely due to its ability to utilize specific flight characteristics for more precise throws. The second scenario showed an initial improvement in the first throw's performance during training, followed by a decline, suggesting an initial learning phase and possible overfitting. The second throw consistently improved, both during training and with unseen planes, underscoring the value of even a single previous trajectory. Unexpectedly, performance declined for later throws, which could be due to insufficient model capacity, inadequate trajectory representations, or overspecialization to specific throw sequences. Qualitative observations suggested a strategy shift, with the first throw often exhibiting high velocity aimed directly at the target, while subsequent throws used lower velocities. This change coincided with the availability of previous trajectory information.

Future research should focus on understanding why information from the first throw improves the second throw's performance, while additional trajectory information appears less beneficial. Ablation studies are recommended to isolate the impact of different trajectory information components. Increasing model size, particularly the VAE component, should be considered if analysis suggests a capacity limitation. Additionally, future work should explore randomizing a broader range of parameters in the paper plane model to increase complexity and generalizability.

Conclusion

Our study demonstrates the effectiveness of combining reinforcement learning with trajectory encoding for optimizing paper plane throwing strategies. The proposed method, integrating a VAE for encoding throw trajectories with an SAC algorithm for action selection, shows improvements over approaches relying solely on environmental information. By incorporating data from previous throws, our model successfully adapts to the unique flight characteristics of individual paper planes, resulting in more accurate throws, especially for unseen designs. However, we observed diminishing returns when using multiple previous trajectories, highlighting areas for future research. These findings not only advance paper plane throwing optimization but also offer insights for broader applications in robotics and dynamic object manipulation tasks.

References

- Ruoshi Liu et al. “PaperBot: Learning to Design Real-World Tools Using Paper”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:2403.09566 (2024).

- Emanuel Todorov, Tom Erez, and Yuval Tassa. “MuJoCo: A physics engine for model-based control”. In: 2012 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems. 2012, pp. 5026–5033. DOI: 10.1109/IROS.2012.6386109.

- Diederik P Kingma. “Auto-encoding variational bayes”. In: arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6114 (2013).

- Tuomas Haarnoja et al. “Soft actor-critic: Off-policy maximum entropy deep reinforcement learning with a stochastic actor”. In: International conference on machine learning. PMLR. 2018, pp. 1861–1870.

- A Vaswani. “Attention is all you need”. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems (2017).

- Antonin Raffin et al. “Stable-Baselines3: Reliable Reinforcement Learning Implementations”. In: Journal of Machine Learning Research 22.268 (2021), pp. 1–8. URL: http://jmlr.org/papers/v22/20-1364.html.

- P Kingma Diederik. “Adam: A method for stochastic optimization”. In: (No Title) (2014).