Probabilistic Logic Guided Soft Sensor Learning via Reward Prediction in Markov Decision Processes

This is a shortened version of my Bachelor’s thesis. The full thesis can be found here.

Abstract

This bachelor's thesis introduces an end-to-end learning framework for the development of soft sensors, which infer hidden variables from available data within Markov Decision Processes (MDPs), offering a novel approach to enhance automation, data efficiency, and environmental independence. Unlike traditional methods that rely heavily on isolated learning and extensive labeled data for each sensor, our framework employs a strategy centered around reward prediction from trajectories, reducing the dependency on labeled data and computational resources. Our methodology is based on the integration of soft sensors into the reward prediction mechanism through the use of customizable probabilistic logic components that describe state transitions and reward formations. This integration of domain expertise and deep learning techniques allows for simultaneous learning of multiple soft sensors in a multi-task learning fashion. The effectiveness of our framework is demonstrated through its application to the Frozen Lake game, where we successfully design and train sensors capable of extracting and interpreting complex information from game states represented as images.

Introduction

Soft sensors, virtual sensors that use data obtained from other sources to predict hidden variables, have become very popular, particularly within the context of enhancing automation, operational efficiency, and the overall quality of products [1], as well as in process monitoring and fault detection [2]. Soft sensors constitute an interesting approach for integrating machine learning algorithms with domain-specific expert knowledge [3].

In this work, a model capable of accurately predicting rewards from given trajectories is constructed. Under the premise that the reward function encapsulates comprehensive environmental information, it becomes possible to concurrently learn various sensors in the background. The primary objective of this thesis is to learn soft sensors through the predictive analysis of rewards. To achieve this, the state-of-the-art framework DeepProbLog [4] is used to embed sensors in expert knowledge formulated in probabilistic logic, leveraging both domain knowledge and deep learning techniques.

We propose a framework designed to learn a plurality of soft sensors simultaneously in an end-to-end fashion. Using a set of trajectories or the underlying MDP, rules for each unique reward are crafted that make use of the sensors. This setup leverages the sensors for reward prediction, making sure they evolve through the learning process themselves. Within this framework, soft sensors can have multiple input data sources of any type. We successfully show the effectiveness of the method in the Frozen Lake game, where we design and learn sensors capable of discerning information from game states depicted as images.

Methodology

In this chapter, we introduce the methodologies employed to develop and refine soft sensors using reward prediction from a given state of a world (for example a grid world) and the agent's position in this world as a strategic tool.

Required Inputs

The method hinges on either directly utilizing a MDP or a set of trajectories derived from the MDP's operation as input data. Specifically, we consider an MDP defined by the tuple $M = (\mathcal{S, A, T, R,}\gamma)$, representing the state space, action space, transition probabilities, reward function, and discount factor, respectively. Alternatively, a set of trajectories represented as $(s_\tau^i, s_{\tau-1}^i, a_{\tau-1}^i, s_{\tau-2}^i, a_{\tau-2}^i,\ldots,s_0^i, a_0^i;r^i)$, can be used, where each trajectory captures a sequence of states, actions and the associated rewards.

Furthermore, the model requires the 3-tuple $(\mathbf{T}, \mathbf{R}, \mathbf{S})$ as input, where $\mathbf{T}$ denotes the transition probabilities expressed in probabilistic logic, $\mathbf{R}$ is the reward function also articulated in probabilistic logic and $\mathbf{S}$ represents a set of soft sensors. $\mathbf{T}$ needs to be designed as a rule that takes all previous actions and outputs the most likely current position. $\mathbf{R}$ is a rule that takes a state and position and outputs the reward for this combination.

Assumptions

For a seamless integration within the framework, we need to make assumptions about the state transition logic, soft sensor design and reward function.

State Transitions: We assume that the state transitions within the environment are known a priori and can be described, or at least approximated, using a probabilistic logic framework. This assumption is fundamental for modeling the dynamics of the system and predicting future states based on past actions.

Soft Sensor Design: The methodology relies on soft sensors for classification, typically implemented as neural networks, to produce a normalized output distribution, such as softmax. Soft sensors for regression tasks cannot be applied. The normalized output format is crucial for the seamless integration of the sensors into the DeepProbLog framework.

Reward Function: It is assumed that the reward function is constrained such that rewards depend solely on the current state, as defined by the agent's position in the world. The rewards have to be discrete because the logic requires a rule for every distinct reward. Moreover, to fully leverage the information contained in entire trajectories, the reward rule is applied recursively, starting from the final state and moving backward through the trajectory. We assume that each interim step in a trajectory provides a reward of 0 until the final state is reached. This approach allows for a cumulative assessment of the trajectory's overall reward based on the sequence of actions taken.

Training Process

The process begins by combining the transition logic $\mathbf{T}$ and the reward logic $\mathbf{R}$ within the framework's logic structure, followed by the embedding of soft sensors into this logic. In cases where an MDP is provided, an agent is learned using a suitable reinforcement learning algorithm. This trained agent is then employed to generate trajectories that serve as data points for further analysis. If a set of trajectories is already available, the data generation phase is bypassed.

Subsequently, these trajectories are utilized to construct queries aiming to predict the most probable reward for given sequences of states and actions, formalized as $P(R = r|s_{\tau}, s_{\tau-1}, a_{\tau-1}, s_{\tau-2}, a_{\tau-2},\ldots,s_{0}, a_{0})$. For each query, the logic program is grounded, a process that includes supplying the necessary inputs to the soft sensors. These sensors then output probabilities for the ground ADs. An important strategy in our training is a recursive use of the reward predictor on preceding states within an episode, anticipating a reward of 0 for all but the final step. This method is intended to enrich the model's understanding of each state's role and significance throughout an episode, rather than isolating its learning to the agent's immediate context. Figure 2 shows the recursive use of the reward predictor.

With a grounded program in place, an SDD is constructed to facilitate the prediction of rewards. The outputs from this SDD are used to compute the loss, which is subsequently fed back into the logic program and, from there, to the sensors to adjust their weights. This feedback loop ensures that the system can iteratively refine its soft sensors.

Upon completing the training process, a set of calibrated soft sensors will be obtained, ready for deployment without being tied to reward prediction metrics.

Experiments

The primary objective of this work is to use DeepProbLog for learning soft sensors on images. For this purpose, we use the "Frozen Lake" game from the gymnasium library. In this work, the game board generation has been changed so that the goal can be in any cell that is not the start. This allows for a better generalization of the soft sensors due to a larger sample variety. The reward is binary, $1$ for reaching the goal and $0$ else. We slightly adjust the reward function so that it gives $-1$ when the agent falls into a hole. This change is done so that the model can better differentiate between different game states to enhance the sensor learning process. To effectively build soft sensors in this setting, our approach involves a multi-faceted input system for the model. It receives a visual representation of the current game state, provided as an image, along with all actions executed before reaching that state and the representations of the previous states. The model's training is focused on predicting the reward based on these inputs.

Data Collection and Preprocessing

The work focuses on learning soft sensors from data generated in a reinforcement learning context using the Frozen Lake game. Rather than training an agent to solve the game, the goal is to create a comprehensive dataset for this purpose. A pre-trained agent employing an ε-greedy Q-Learning approach is used to generate data, ensuring good exploration of the game board while still reaching cells near the goal. Data is collected from multiple randomly generated game boards with varying hole locations and goal positions. Each data point includes the states (as images) the agent has seen, actions taken, and the reward received in the last step.

Due to the nature of the game, the resulting dataset is imbalanced, with most data points having a reward of 0, fewer with -1 (falling into a hole), and even fewer with 1 (reaching the goal). To address this imbalance, a combination of under- and oversampling techniques is applied. The images are preprocessed by converting to grayscale using the luminosity method and then normalized to values between 0 and 1. Two datasets are generated: one using deterministic state transitions and another using stochastic state transitions in the game.</p>

Model

Our model integrates three principal components: (1) neural predicates as a connector between the probabilistic logic model and the neural networks (2) a deterministic transition model modeling the state transitions and (3) a reward predictor. The transition model is used for position estimation, predicting the agent's current position given a start position and all the actions the agent has taken so far.

Neural Predicates

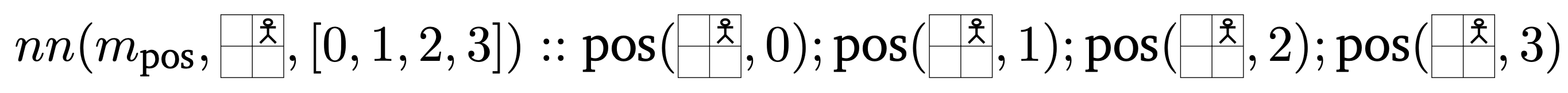

Our model employs six neural predicates, categorized into two distinct types, based on their input requirements and predictive capabilities. The first type includes predicates that analyze the image of the current state to make predictions about the scene as a whole. Within this group we have predicates designed to (1) identify the agent's position within the grid, (2) determine whether the agent is standing on the goal position (is_on_goal), (3) check whether the agent fell in a hole (is_on_hole) and one for determining the goal position (goal_position). For instance, in a $2 \times 2$ game board, the neural predicate $m_\text{pos}$ predicting the agent being in cell $1$ can be formalized as

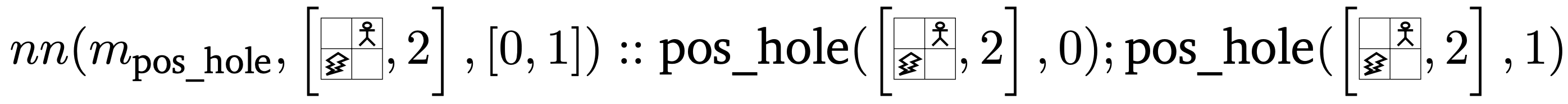

Predicates in the second category require both the image of the current state and a specific position as inputs, allowing them to make predictions about individual cells in the grid world. This type of predicate is used to (1) check for the presence of a hole in a specified cell (position_hole) and (2) to evaluate whether a particular cell represents the goal (position_goal). Taking the $2 \times 2$ grid world example again, the neural predicate $m_\text{pos_hole}$ predicting whether position $2$ is a hole can be formalized as

Soft Sensors

Our model utilizes neural predicates, each equipped with a dedicated soft sensor for classification implemented as a neural network. The architecture follows an encoder-decoder paradigm. A shared convolutional encoder, consisting of two convolutional layers, extracts essential features from input images. This shared encoder allows for learning meaningful representations across different tasks. Task-specific decoders, constructed as Dense Networks, interpret the encoded features and produce targeted predictions. All decoders use a softmax layer to output probability distributions over possible classes. There are two types of decoders:

-

The first type operates solely on encoder-generated features. These decoders predict positions (outputting a distribution over all possible positions) or binary outcomes (e.g., whether the agent is on the goal or in a hole).

-

The second type incorporates specific positions into the prediction process. Instead of using the whole image, only the cell of interest is passed to the decoder, resized to maintain encoder compatibility. These decoders output binary probability distributions for task-specific conditions at given positions.

This architecture enables the model to learn meaningful representations across different tasks while allowing for task-specific predictions, adapting to the grid-like nature of the environment and addressing various prediction requirements.

Reward Predictor

The reward predictor is a key component of the model, responsible for determining the rewards an agent receives in various states. It functions by combining deterministic information from the transition model with predictions from neural predicates. The reward determination process considers three distinct scenarios, each contingent on the outputs of several neural predicates.

When the agent reaches the goal, it receives a reward of 1. This occurs when the predicates indicate the agent is on the goal, not in a hole, and the current position matches the goal position. Conversely, a reward of -1 is given when the agent falls into a hole, as indicated by predicates showing the agent in a hole, not on the goal, and at a position identified as a hole. In all other cases, where the agent is neither on the goal nor in a hole, a reward of 0 is assigned.

The model utilizes the agent's history of actions to predict its current position, which is then used in conjunction with these neural predicates to ascertain the appropriate reward. This sophisticated system enables a nuanced understanding of the agent's state and performance within the environment, allowing for accurate reward allocation based on the agent's actions and position relative to goals and hazards.

Training Process

Two separate training sessions on the model are conducted, each lasting 15 epochs. The first session utilizes the deterministic training data, while the second session uses the stochastic training data, presenting a more challenging scenario to test if a model using deterministic state transitions can make good predictions under uncertainty too. The model is trained using the ADAM optimizer with a learning rate of $10^{-5}$. It has been found that within the DeepProbLog framework a very small learning rate is beneficial. Additionally, to enhance the encoder's learning of representations, we incorporated auxiliary task learning, specifically for predicting the agent's position. This task's complexity varies with the training data, being straightforward with deterministic data due to predictable outcomes and the availability of concrete ground truth from the deterministic transition model. The encoder, designed to be task-independent and shared across all predictors, is refined using the position prediction task, illustrating how auxiliary tasks can serve as indirect mechanisms for boosting overall task performance.

Results

Unfortunately, the DeepProbLog framework does not support the tracking of individual neural predicates' losses but only for the complete model. This limitation necessitates a manual evaluation process for our soft sensors that calculates key metrics for each sensor on both the training and testing sets. Given our focus on the distinct performance of each sensor, this individualized evaluation is a critical component of our analysis.

| Soft Sensor | Deterministic Training Data | Stochastic Training Data |

|---|---|---|

| Agent Position | 0.9972 | 0.3165 |

| Agent on Goal | 1.0000 | 0.9944 |

| Agent on Hole | 0.9916 | 0.9860 |

| Goal Position | 0.7283 | 0.0420 |

| Position is Goal | 1.0000 | 0.9597 |

| Position is Hole | 0.9988 | 0.7626 |

| Soft Sensor | Deterministic Training Data | Stochastic Training Data |

|---|---|---|

| Position is Goal | 1.0000 | 0.3557 |

| Position is Hole | 1.0000 | 0.0486 |

Results for Deterministic Training Data

When trained on deterministic training data, the model demonstrated excellent performance in reward prediction. This high level of accuracy indicates that the model's soft sensors learned effectively from the deterministic data, with almost perfect predictions across the board, except for the sensor predicting the goal's position. A breakdown of the accuracy achieved by each sensor on the test set is shown in Table 1 Additionally, figure 5a depicts the training loss for the reward predictor, while figure 6 presents the training losses for each sensor throughout the training process. In figure 8a the confusion matrix for the position prediction is shown. It can be observed that the prediction is correct for most samples (the points lie on the diagonal) but the prediction for position 15 is not yielding good results.

Results for Stochastic Training Data

When the agent is trained on stochastic training data, a different pattern can be observed. Although the loss does not decrease as smoothly as with deterministic data, the model still achieves a respectable 83% accuracy in reward prediction. The loss curve is displayed in Figure 5b. This suggests a robustness to stochasticity, with certain soft sensors, such as is_on_goal and is_on_hole displaying accuracies potentially sufficient for accurate reward prediction. The sensor-specific accuracies are again shown in Table 1. The accuracies of networks determining whether a cell is a hole (position_hole) or the goal (position_goal) are also high, albeit somewhat misleading. This is because the accuracy is calculated across all cells, and when focusing solely on cells that actually contain a goal or hole, the accuracy for these predictions drops significantly, especially for position_hole predictions, see Table 2 for more details. This behavior indicates that these sensors tend to predict that there is no goal/hole in almost all cases. Analyzing the sensor-specific losses in figure 7 we observe that only the losses for is_on_goal and is_on_hole drop significantly. The loss for the other sensors is going down only very slowly, or even oscillates.

This discrepancy underscores the challenges posed by stochastic game transitions on the model's predictive capabilities. Particularly, the deterministic transition model used by our system struggles to accurately predict the agent's position in longer action traces, given the stochastic nature of the game data. This inaccuracy in position prediction directly impacts the learning of the position sensor and the networks responsible for predicting if specific cells are the goal or holes within the game environment. Figure 8b illustrates this through a confusion matrix for the position prediction after training, showing that while the model accurately predicts positions closer to the starting point, it becomes increasingly inaccurate for positions further away. This outcome highlights the limitations of relying on a deterministic transition model in a stochastic setting and suggests avenues for further research in improving model robustness and predictive accuracy.

Discussion

The model demonstrates high accuracy in reward prediction and soft sensor performance when trained on data from a deterministic environment. This aligns with expectations given the deterministic nature of the underlying MDP. Position prediction is generally accurate, with a notable discrepancy at position 15, attributed to the distribution of the agent's final positions in the dataset. The balancing measures implemented focus on equilibrating rewards, neglecting the balance of game board properties like agent position.

In stochastic environments, the model faces difficulties in accurately tracing agent movements due to the incompatibility between the stochastic environment and the deterministic transition model. Despite this, reward prediction remains highly accurate, primarily due to two sensors that reliably determine if the agent has reached a goal or fallen into a hole. These sensors directly capture immediate outcomes associated with the last observed state, receiving strong and consistent training signals.

Position prediction performs better for locations near the starting point for two reasons: initial steps are less affected by environmental randomness, and the data distribution is skewed towards early-game positions due to reward-based balancing and game randomness.

Switching our model's current deterministic transition model to a stochastic transition model is theoretically possible, but the implementation in practice is challenging. The main issue is that the number of potential outcomes explodes dramatically. Every time the agent makes a move, it could not only proceed as planned but also slip away perpendicularly. This situation means that for every single action, there are three possible outcomes. Considering a sequence of actions, the complexity grows exponentially, for $n$ actions there are $3^n$ potential paths to consider. This massive increase in the number of potential states makes it incredibly challenging to predict the outcome of even a relatively short sequence of actions.

Conclusion

In this thesis, we have introduced a complete end-to-end learning framework for training soft sensors. We base our learning process on the reward predictions of trajectories generated in MDPs. Therefore, the framework has customizable probabilistic logic components and any number of fungible soft sensors. The logic components are used for describing the state transitions and to determine how rewards are composed. Once set up, the framework can take a MDP or a set of trajectories generated within this MDP and predict the corresponding final reward for each trajectory. During the estimation process, it leverages the output of the transition model and the predictions of the soft sensors. The reward prediction loss is finally used to initialize backpropagation of the sensors. By solely focusing on the reward prediction, our approach overcomes the need for soft sensor-specific training data. We successfully applied our framework to the Frozen Lake game, training sensors to extract features from the game board. However, we also recognize limitations in using our framework in stochastic environments since the integration of a stochastic transition model within the logic components presents a non-trivial challenge.

Future work on this framework encompasses several key areas: refining the learning strategy for stochastic environments by segmenting trajectories and improving starting position determination; developing methods for automatic adjustment of sensor architectures to enhance adaptability; expanding the framework beyond position-based learning to incorporate a broader range of environmental attributes; enhancing the Sentential Decision Diagram's capabilities for better class separation and prediction; removing reliance on pre-existing environmental knowledge; adapting the system for large-scale, complex environments through dynamic knowledge bases and continuous learning loops; and improving the framework's ability to handle unknown or partially known reward functions.

Bibliography

- Yueyang Luo et al. “Data-driven soft sensors in blast furnace ironmaking: a survey”. In: Front Inform Technol Electron Eng 24.3 (Mar. 1, 2023), pp. 327–354. issn: 2095-9230. doi: 10.1631/FITEE.2200366.

- Yasith S. Perera et al. “The role of artificial intelligence-driven soft sensors in advanced sustainable process industries: A critical review”. In: Engineering Applica- tions of Artificial Intelligence 121 (May 1, 2023), p. 105988. issn: 0952-1976. doi: 10.1016/j.engappai.2023.105988.

- Qingqiang Sun and Zhiqiang Ge. “A Survey on Deep Learning for Data-Driven Soft Sensors” In: IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 17.9 (Sept. 2021), pp. 5853–5866. issn: 1941-0050. doi: 10.1109/TII.2021.3053128.

- Robin Manhaeve et al. “DeepProbLog: Neural Probabilistic Logic Programming”. In: Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems. Ed. by S. Bengio et al. Vol. 31. 2018. url: arXiv:1805.10872.